The Illusionist is an act of cinematic reincarnation. It is based on a screenplay originally written by Jacques Tati, who died in 1982, but in Sylvain Chomet's film, the French artist takes centre stage once again in animated form. It feels like a Tati film in so many respects; not only because of the unmistakable figure of the man himself, but because of the complex soundtrack of mostly incomprehensible chatter, the layering of sight gags into both the background and foreground of the action, and the main protagonist's befuddlement at the technologies of the modern age. The Illusionist also bears the distinctive mark of Chomet, however, with the animator using old-fashioned techniques to find moments of great beauty in this surprisingly melancholy tale.

The Illusionist is an act of cinematic reincarnation. It is based on a screenplay originally written by Jacques Tati, who died in 1982, but in Sylvain Chomet's film, the French artist takes centre stage once again in animated form. It feels like a Tati film in so many respects; not only because of the unmistakable figure of the man himself, but because of the complex soundtrack of mostly incomprehensible chatter, the layering of sight gags into both the background and foreground of the action, and the main protagonist's befuddlement at the technologies of the modern age. The Illusionist also bears the distinctive mark of Chomet, however, with the animator using old-fashioned techniques to find moments of great beauty in this surprisingly melancholy tale.

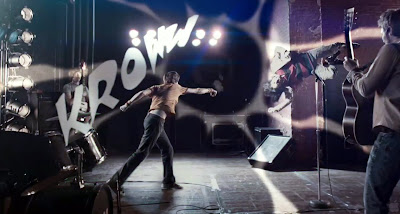

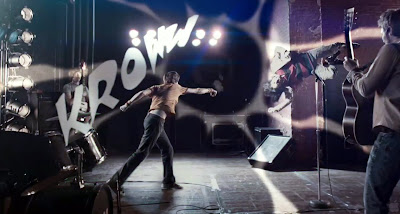

The core of sadness that lies at the heart of The Illusionist was the reason that Tati decided against filming his screenplay in the early 1960's and decided instead to focus Playtime, the epic 1967 film that would cause irreparable damage to his reputation. Who knows how his career would have developed if had instead proceeded with this more intimate and personal tale? In The Illusionist, the central character of Tatischeff (Tati's real name) is an ageing vaudeville conjurer struggling to make ends meet in the music halls of Paris at the end of the 1950's. He travels to a grey and wet London to see if he can revitalise his career there, but he discovers his act is even more irrelevant in a city swooning over the Beatles-like sensation of Billy Boy and the Britoons. Tatischeff waits patiently in the wings while they perform to a crowd of screaming teens, but by the time he has taken to the stage, the auditorium has emptied, leaving a few disinterested stragglers for him to perform to.

Chomet's film is a lament for a lost era of entertainment, but Tatischeff does find an appreciative audience when he travels to Scotland, with a young girl being so enamoured with his trickery that she accompanies him to Edinburgh. She completely believes in the illusions he pulls off so effortlessly, but when she asks him to conjure a new dress or pair of shoes, she has no idea that he has to scrape together his pennies in order to do so, or that he has to find a series of demeaning jobs to make ends meet. It's hard out there for a variety act, and Chomet balances his film's humour with an air of despondency, occasionally straying from Tatischeff to focus on his suicidal and alcoholic fellow performers, all of whom are finding that their skills are suddenly no longer required.

Frustratingly, however, The Illusionist stumbles somewhat between the two stalls of comedy and tragedy, and fails to leave a particularly lasting impression in both respects. The jokes are the kind that raise an occasional smile – Tatischeff's battles with his uncooperative rabbit are fun, and Chomet has a great gift for populating his film with instantly recognisable and memorable archetypes – but few of the film's comic set-pieces really stand out. Chomet's last film was the marvellous Belleville Rendez-Vous, which was ripe with invention and energy, but The Illusionist's more sombre tone sometimes drags, and the film peters out towards the climax, when the sense of loss and disappointment really should resonate.

It's a gorgeous film to look at, though, with every shot benefitting from Chomet's eye for detail and atmosphere. After creating a vividly exaggerated world for Belleville Rendez-Vous, Chomet here produces some wonderfully evocative recreations of Paris, London and Edinburgh from a bygone age, and throughout the picture he proves himself to be a filmmaker in complete command of his art. The most affecting moments in The Illusionist occur when Chomet's brilliant animation succeeds in creating a sense of illusion and wonderment; turning feathers from an open pillowcase into an unlikely snowstorm, or making the shadow cast by pages in a book resemble the silhouette of a bird in flight. Perhaps the film's most remarkable scene comes when Tatischeff blunders into a cinema screening Mon oncle, and for a few surreal seconds, the real and imagined Tati gaze at each other through the dark. "Magicians do not exist," Tatischeff writes in one of the film's most downbeat moments, but anyone watching Chomet cast his spell will beg to differ.

As I watched the outstanding Chilean film The Maid, I anticipated a certain kind of story, but instead I was presented with something so much funnier, darker, more complex and more surprising than I could have imagined. I thought Sebastián Silva's film was going to be a straightforward examination of the class divide, with its central character being a maid who has loyally worked for the same wealthy family for over twenty years, but Raquel (Catalina Saavedra) has a habit of tripping up our expectations. The Valdez family treat their veteran made with kindness and patience, doing what they can to make her feel part of the family, and the opening scene finds them throwing her a birthday party. Raquel, however, refuses to budge from the kitchen, and when they finally persuade her to come and accept her gifts, she does so in a surly fashion before quietly getting back to her work. "You don't have to do the dishes now," the matriarch Pilar (Claudia Celedón) insists. "If I don't do them now I'll just have to do them later," Raquel morosely replies.

As I watched the outstanding Chilean film The Maid, I anticipated a certain kind of story, but instead I was presented with something so much funnier, darker, more complex and more surprising than I could have imagined. I thought Sebastián Silva's film was going to be a straightforward examination of the class divide, with its central character being a maid who has loyally worked for the same wealthy family for over twenty years, but Raquel (Catalina Saavedra) has a habit of tripping up our expectations. The Valdez family treat their veteran made with kindness and patience, doing what they can to make her feel part of the family, and the opening scene finds them throwing her a birthday party. Raquel, however, refuses to budge from the kitchen, and when they finally persuade her to come and accept her gifts, she does so in a surly fashion before quietly getting back to her work. "You don't have to do the dishes now," the matriarch Pilar (Claudia Celedón) insists. "If I don't do them now I'll just have to do them later," Raquel morosely replies.

The truth is that the 41 year-old has become worn down by her years of hard work and selfless devotion, and soon she is suffering from debilitating headaches and blackouts, but when Pilar decides to hire another made to share the workload, she unwittingly lights a dangerous fuse. The moment Mercedes (Mercedes Villanueva) sets foot on the property, Raquel makes it her mission to drive the young girl away. She torments her, locks her out of the house and even scrubs down the bathroom with powerful disinfectants whenever the bemused and scared Mercedes has taken a shower. She does everything in her power to reclaim her position of dominance within the household. This is Raquel's territory, and she's not giving it up without a fight.

As her behaviour becomes increasingly unreasonable, The Maid becomes something of a psychological thriller laced with a healthy dose of black comedy. Silva's beautifully structured screenplay zags when you expect it to zig, and he develops a riveting sense of tension as Raquel engages in an absurd battle of wills with a succession of maids. Even as the film strays into more outlandishly comic territory – like Raquel hiding a cat in a drawer, or the second new maid Sonia (Anita Reeves) being reduced to clambering over the rooftops – Silva makes sure it all develops in a natural fashion and that it remains rooted in a believable sense of humanity. Perhaps Silva's prime skills as a filmmaker lie in his writing rather than his directing, as The Maid is shot in a drab and sometimes clumsy fashion, but he does enough to wring plenty of mileage out of his script, and he draws superb performances from his actors.

Above all, the central performance from Catalina Saavedra is an astonishing piece of work. It's a brilliantly complex portrayal, simultaneously fearsome and funny, and as the film progresses she allows us to see behind the character's gruff exterior to examine the root cause of her extreme behaviour. Having spent two decades living and working with this family, Raquel has nobody else in her life and she has become emotionally stunted through her lack of experience of the outside world. When her role as the Valdez family's maid is threatened she fears she's about to lose everything, so she reacts in the only way she knows how, fighting tooth and nail to scare off any competitors. Even as Raquel burns with vindictive intent, however, Saavedra finds room for moments of tenderness in her performance; she really does love this family, she just has an unusual way of showing it.

That's why the final section of the film is so satisfying. When Pilar tries for the third time to find an assistant who Raquel can work alongside she hits the jackpot with Lucy (the brilliant Mariana Loyola), a young maid who stands her ground against Raquel's aggressive tactics. Lucy's no-nonsense approach and her determination to connect with Raquel gives the older maid an opportunity to develop a real friendship for the first time in many years, and when she finally allows her grumpy visage to relax into an uneasy smile, there's a genuine sense of revelation. The Maid takes us on a real journey with Raquel, who, thanks to Silva's perceptive writing and Saavedra's extraordinary display, is one of the year's most intriguing and entertaining screen characters. When we finally leave her, striding purposefully towards the camera, it feels like we've witnessed nothing less than a woman reborn.

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo wasn't a great film, but it had a sense of style, some slick editing and it told a moderately intriguing story. None of these qualities can be applied to the film's slapdash sequel, The Girl Who Played with Fire. This is the second screen adaptation of Stieg Larsson's Millennium Trilogy but it already feels like the wheels have started to come off, and despite being a shorter film than its predecessor, The Girl Who Played with Fire feels senseless and interminable. Having not read Larsson's novels, I don't know how much of this is down to the simple fact that the source material is weaker this time around, but I do think a lot of the blame has to lie at the feet of director Daniel Alfredson.

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo wasn't a great film, but it had a sense of style, some slick editing and it told a moderately intriguing story. None of these qualities can be applied to the film's slapdash sequel, The Girl Who Played with Fire. This is the second screen adaptation of Stieg Larsson's Millennium Trilogy but it already feels like the wheels have started to come off, and despite being a shorter film than its predecessor, The Girl Who Played with Fire feels senseless and interminable. Having not read Larsson's novels, I don't know how much of this is down to the simple fact that the source material is weaker this time around, but I do think a lot of the blame has to lie at the feet of director Daniel Alfredson.

He's a newcomer to this series, picking up the reins from Niels Arden Oplev, who did a creditable job on the original. It is not a change for the better as Alfredson seems to lack any sense of vision or storytelling momentum. He takes an age to set the story in motion and he almost loses his way in the opening minutes, with a flurry of flashbacks and subplots clouding the issue. This time around, the story sees computer hacker Lisbeth Salander (Noomi Rapace) being framed for multiple murders and going on the run, with investigative journalist Mikael Blomkvist (Michael Nyqvist) doing his bit to help clear her name. There's also an investigation into a sex-trafficking ring, revelations about Lisbeth's father, a lesbian sex scene (the only time Alfredson seems to really take some care over his composition and lighting), some very impressive record-keeping from a German amateur boxing club, and an Aryan giant impervious to pain who seems to have wandered in from a 1980's Bond movie.

Jesus, it's boring even to type this. The screenplay by Jonas Frykberg (who also had nothing to do with the first film) joins these dots in the most unimaginative manner possible – a quick search on Google solves most problems – and some of the twists are beyond ridiculous. The film never coheres and it just unfolds flaccidly onscreen as a series of disconnected incidents driven by silly coincidences and clichés. A better director than Alfredson may have been able to gloss over some of these deficiencies, but his choice of camera angles, his use of slow-motion and his sense of mise-en-scène is utterly generic from first frame to last. The grey and washed-out cinematography utilised makes every scene look dreary, and I began to wonder if the same flaws that cripple The Girl Who Played with Fire were present in the first film but were smartly hidden by the sleek production. Certainly, Larsson's habit of painting every male character as either a noble do-gooder or a sick, abusive bastard is horribly exposed second time around.

The film only has one real asset in its favour, with Noomi Rapace reprising her role as The Girl Who Should Be in a Better Film. There has been much talk in recent weeks about the various actresses up for the role of Lisbeth in the forthcoming (and completely unnecessary) US version of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, but I doubt any of the women considered will have the same impact that Rapace has had in the part. She brings a great sense of dark mystery to the troubled avenging angel Lisbeth, and even while her character is often short-changed here by not having enough interesting things to do, Rapace remains a fascinating and magnetic presence. Her contribution isn't quite enough to hold this barely competent film together, though, and I had completely lost all interest by the time the film finished in an amusingly abrupt fashion (it's as if everyone involved suddenly decided that they'd wasted enough of our time already). Frankly, it's hard to give a damn about what may lie ahead in the third episode The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest, which is due for release in November. I have been reliably informed that the final book in the series is the worst of the three, and with Alfredson once again sitting in the director's chair, even the return of Rapace in the role she has made her own isn't enough to stoke my anticipation levels.

It's very easy to be dazzled by Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, but alas, the effect is fleeting. Edgar Wright's film is a visual onslaught, with almost every scene being embellished in some way by a caption, gag or special effect. When a phone rings, we see R-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-NG blare across the screen; when one character declares her love for another, the word "love" emerges from her mouth as a puff of pink smoke that her would-be partner wafts away; when Scott (Michael Cera) kisses Ramona (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), tiny pink hearts fly out from their locked lips. Edgar Wright developed his high-impact, heavily referential directorial style on the TV series Spaced and his two features Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz, and he has raised his game here, making every camera move, sound effect and piece of trickery count. Unfortunately, a little of this goes a very long way, and in Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, there's a lot of it.

It's very easy to be dazzled by Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, but alas, the effect is fleeting. Edgar Wright's film is a visual onslaught, with almost every scene being embellished in some way by a caption, gag or special effect. When a phone rings, we see R-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-NG blare across the screen; when one character declares her love for another, the word "love" emerges from her mouth as a puff of pink smoke that her would-be partner wafts away; when Scott (Michael Cera) kisses Ramona (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), tiny pink hearts fly out from their locked lips. Edgar Wright developed his high-impact, heavily referential directorial style on the TV series Spaced and his two features Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz, and he has raised his game here, making every camera move, sound effect and piece of trickery count. Unfortunately, a little of this goes a very long way, and in Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, there's a lot of it.

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World is Wright's adaptation of a series of Toronto-based comic books by Bryan Lee O'Malley. The film is a love story, of sorts, but its title character is a tough figure to get behind as a romantic lead. Scott is a 22 year-old slacker who plays bass in a mediocre band called Sex Bob-omb and he's currently dating a rather sweet 17 year-old high school student called, for some reason, Knives (Ellen Wong). As played by Cera, Scott is whiney, indecisive and selfish, and he's ready to drop Knives like a hot potato the moment he lays eye on Ramona, the enigmatic and beautiful character who is (literally) the girl of his dreams. If he wants to win Ramona's heart, however, he'll have to fight for her, as her Seven Evil Exes suddenly start turning up to challenge Scott to a series of duels.

So there's your narrative; a series of fights between a super-powered Scott and his colourful array of assailants – Seven of them, for God's sake. Actually, mercifully, there are only six bouts to sit through, as two of Ramona's exes are twins whom Scott needs to tackle at the same time. Your mileage may vary, but after a couple of these encounters, I'd already seen enough. The fights in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World are modelled on videogames, with the characters flying through the air at each other, smashing through walls and finally, when one has been vanquished, exploding into coins. This sudden change of pace and the imbuing of Scott with unimaginable fighting abilities are never explained, and these sequences simply explode out of the movie in same manner and song-and-dance numbers would in a musical, but how seriously are we meant to take them? At the end of every bout, Scott kills one of Ramona's exes (well, he turns them into coins), but there is no sense of life and death at play here. The battles feel weirdly inconsequential and, as inventively as they have been made, they ultimately feel rather dull.

Which begs the question: if we don't care about these battles, then why should we care about the love that Scott is fighting so valiantly for? As a romance, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World is damp squib. Michael Cera's ineffectual performance is not strong enough to hold the centre of the film, and as Ramona, Mary Elizabeth Winstead is never allowed to be anything more than a pair of pretty eyes underneath a colourful wig. In fact, nobody in the large and talented cast is allowed to play anything other than a single note repeatedly. Some of them do a lot with the little they've been given – Chris Evans and Brandon Routh are probably the funniest of the Exes, while Kieran Culkin's deadpan comic timing is one of the movie's unqualified highlights – but they aren't really characters, they're just individuals with a single trait to offer.

So, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World is all style, and the style is often thrilling to watch. Edgar Wright is a hugely talented filmmaker with a keen eye for sight gags and real sense of confidence in his ability to wield a camera. The film is very, very funny in places, and some of its imaginative touches are delightful, but there's also something unappealingly self-conscious about the manner in which the film cloaks itself in pop-culture references while never connecting with anything below the surface. Ramona's habit of changing her hair colour on a weekly basis reminded me of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and the comparison didn't help Scott Pilgrim's cause. That picture complemented its wild and imaginative flights of fancy with a story grounded by real emotions, whereas I didn't for one moment feel anything as I watched Scott's pursuit of Ramona. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World has so much technical wizardry at its disposal, it has a hugely talented cast and crew on board, it has an encyclopaedic knowledge of movies, music, computer games and comics – the one thing it's lacking, sadly, is a heart.

The advertising campaign for Salt has repeatedly asked a single question: Who is Salt? Well, depending on who you believe, Evelyn Salt is a highly trained but otherwise ordinary CIA operative or an undercover Russian spy planning to commit a political assassination (or both). Similarly, depending on who you ask, Phillip Noyce's film is a silly and clichéd piece of nonsense or a beautifully made and generally riveting thriller (or both!). In judging the film, I tend to slide towards the positive camp, even if I can see the picture's glaring flaws. As soon as the film had finished I began to analyse the plot in my head, and it immediately fell to pieces as I questioned the motives and decisions made by the characters, and some of the twists concocted by screenwriter Kurt Wimmer. But all of that took place after the movie, and for every one of Salt's pleasingly efficient 100 minutes, I was gripped.

The advertising campaign for Salt has repeatedly asked a single question: Who is Salt? Well, depending on who you believe, Evelyn Salt is a highly trained but otherwise ordinary CIA operative or an undercover Russian spy planning to commit a political assassination (or both). Similarly, depending on who you ask, Phillip Noyce's film is a silly and clichéd piece of nonsense or a beautifully made and generally riveting thriller (or both!). In judging the film, I tend to slide towards the positive camp, even if I can see the picture's glaring flaws. As soon as the film had finished I began to analyse the plot in my head, and it immediately fell to pieces as I questioned the motives and decisions made by the characters, and some of the twists concocted by screenwriter Kurt Wimmer. But all of that took place after the movie, and for every one of Salt's pleasingly efficient 100 minutes, I was gripped.

Salt succeeds because it doesn't allow its propulsive momentum to slacken. The plot kicks into gear early on, with Evelyn Salt (played by Angelina Jolie) being identified as a Russian spy by the KGB defector (Daniel Olbrychski) she is interrogating. Her colleague Ted Winter (Liev Schreiber) doesn't believe a word of it, but Counterintelligence agent Peabody (Chiwetel Ejiofor) wants to do things by the book and hold her for questioning – some chance. As soon as Salt's identity becomes the subject of debate, she's out of there, fashioning a handy explosive device, MacGyver-style, and breaking past the SWAT team sent to take her down with consummate ease. She races into the street with Winter and Peabody in pursuit and her motives unclear. Is she planning to kill the visiting Russian President, or is she just a desperate woman out to clear her name?

The obvious antecedent for Salt is the Bourne movies, with this film's protagonist outthinking, outfighting and outrunning her pursuers in a manner that feels very familiar. What distinguishes Salt from those pictures is the measured directorial style of Phillip Noyce, which is the polar opposite to the hectic, rapidly edited handheld approach of Paul Greengrass. With two Jack Ryan adaptations under his belt, Noyce is an old hand at this kind of political thriller, and with Salt he keeps the action coherent and slick while maintaining a lively tempo. Aided by fine camerawork from the ever-excellent Robert Elswit and James Newton Howard's imposing (and undeniably Bourne-like) score, Noyce stages some superb, fluid action sequences here. The long motorway chase scene is pulled off with real panache, as is a late assault on a less-than-secure White House bunker, but Noyce's wisest filmmaking choice is to recognise that his greatest asset is his leading lady.

This is a great movie star performance from Angelina Jolie. Salt was conceived as a vehicle for Tom Cruise, but when he pulled out, the decision to rewrite the lead character and give it to Jolie was a masterstroke. While utterly convincing as a woman who can go toe-to-toe with any male antagonist and win, she also brings a gracefulness and vulnerability to the role that freshens up the potentially mundane plot. Noyce frames her like a star, frequently resting his camera on her face to let her play the character's ambiguity, and she responds with a magnetic central performance driven by her extraordinary screen charisma. Salt may be built around a narrative that feels like it has been ripped out of an early-90's thriller (Russians! Double agents! Nuclear war!), but Noyce ensures it never skips a beat, and Jolie's presence is enough to make it seem like something excitingly new.

Is Bong Joon-ho the most exciting director of his generation? Few other filmmakers can match his sense of craftsmanship, his flair for storytelling and his extraordinary range, and his new film Mother is his finest work yet. I was thrilled to have the opportunity recently to email some questions to the director about Mother and his remarkable body of work. Here are the answers he sent back.

Is Bong Joon-ho the most exciting director of his generation? Few other filmmakers can match his sense of craftsmanship, his flair for storytelling and his extraordinary range, and his new film Mother is his finest work yet. I was thrilled to have the opportunity recently to email some questions to the director about Mother and his remarkable body of work. Here are the answers he sent back.

How did it feel to go back to a smaller, more intimate type of storytelling after a big, effects-heavy blockbuster like The Host?

The Host was a movie like a showroom of satire. It contained a wide range of satire on both USA and Korean society. As the reaction to this, in Mother I would like to focus more on points such as the presence of the mother itself, the relationship between mother and son. However, I already had a storyline for Mother before I completed the scenario of The Host. I have prepared for this movie from 2004, so it depended on what I want to say rather than the scale of the movie. It was a personal line-up planned by my desire of expression.

Kim Hye-ja's performance in the film is incredible. How did she react when you first approached her with the script?

I told Kim Hye-ja the storyline of Mother in 2004. I worried a lot because this movie could not be continued if she declined my offer. I made this story and scenario while thinking of Kim Hye-ja, so there was no substitute. Fortunately, she liked the story and said she would like to take the role, saying this role was different from other mothers she had performed, and I remember I breathed a sigh of relief when she said that. When I showed her the completed scenario in 2008, she mentioned the fogbound atmosphere and that she liked this mysterious and dreamy atmosphere. Thankfully, she said that something more was hidden in the character of mother and she would do more than what was being portrayed in the scenario.

Is the role of the mother a particularly important one in Korean society? In The Host, the mother was notably absent from the family, so is this film a reaction to that?

Not just in Korean society, a mother’s role is paramount throughout the world. Yet we Koreans are obsessed with motivations to move the society into a better place and the society expects mothers to go beyond, especially with an issue that is related to their children, and it causes them to have more burdens. In the movie The Host, the story is based on one family, but the mother was never involved in the story. The mother's absence was definitely intentional because the absence brought problems to the family and made the family unstable. Not just Song Kang-ho's wife, but also Byoun Hie-bong's wife ran away; hence, the family lost mothers for two consecutive generations to make the family even more miserable. It was planned to see and realise the importance of a woman's role in the family. I think a mother is the most influential existence in the family, and because of the mother's absence, this family was a mess. Even Hyun-seo, the girl in the hideout of the Host, was the pre-image of a mother. That's why I ended up making my next film based on a mother.

The mother's love for her son is so strong it seems to border on the edge of insanity. Is that kind of obsessive love something you wanted to explore with this film?

Yes, right. When love crosses a certain line it turns to obsession or madness and it also can be a sin. Especially when it comes to the relationship between mother and son, it is closer to the strong basic instinct. Basically, it starts as love, but it can be changed to something animal rather than humanlike – a growling tiger with its claws out to save her cub. It could be madness and brutality from the viewpoint of a human, and I would like to show something like that in this movie.

How did you come up with the idea for the dancing that opens and closes the film?

That ending sequence, in which she dances inside a running express bus, could be a kind of Korean reality. In Korea, middle-aged women often dance inside express buses. I have witnessed it quite often. I don't remember when, but I've long been determined to make dancing in the express bus as a core image when making a film about a mother. Korean mothers dancing in the bus contains mixed emotion and complex feelings. I wonder whether this could be translated into English, but anyway, I've had the image of the ending sequence from the beginning. I remember that I told Kim Hye-ja about the dance even when I was explaining to her the simple storyline.

The dance at the opening sequence is something that came to my mind while I was finishing the script – how about beginning it with a dance? But the site in which the dance takes place has some sense of horror. It may seem like a plain, beautiful field at first, but as we watch the film for two hours, we realize that it's the place which the mother arrives at after committing something terrible.

I’m always amazed by the way your films successfully mix scenes of drama and violence with comedy. Is it hard to achieve this balance between conflicting emotions?

Actually, that kind of mix is my instinct. I have never arranged scenes intentionally, but it just mixes like that when it is complete. I think that it would be more natural, because emotions cannot be defined as just one. I insist that this way with mixed feelings is more realistic.

The script for Mother is very tightly structured and it contains a number of twists and surprises. What is your writing process and how long does it take you to develop your screenplays?

It’s quite an inclusive question, so it’s hard to answer briefly. For example, Memories of Murder took 6 months of research, which was quite a long time, and I wrote the script for 6 months. The Host took 6 months to a year to write. In the case of Mother, I collaborated with a writer, Ms. Park Eun-kyo. While I was filming The Host, Ms. Park did primary works according to the storyline which I wrote, and then I finalised the script. It took about 5 months to finish the script by myself. Writing a scenario is such a complicated process, there are lots of things that make me agonise in loneliness. Now I’m alone working on the adaptation of Transperceneige, which is torturing me at times. When I’m stuck on it, I sometimes feel like killing everyone besides me and then killing myself!

What is your directing style like? Do you storyboard prior to shooting, and how do you work with actors on set?

I draw my storyboards by myself. I try to settle the site and space in advance, so that I can have some understandings or feelings about that space when working on the storyboard. Space, as well as character, is important to me, and without the space, I cannot work on the storyboard. I precisely design the position and movement of camera and the frames. For actors I tend to be more generous. They're human beings, unlike cameras or lighting, so it's a matter between a human and a human. When they show me unexpected stuff, I am most satisfied. Of course, I sometimes direct or ask them to act in certain ways, but the most delightful moments are the moments when actors show me a surprise with their own instinct as actors. I prefer those improvisations, and I try to make various attempts; changing the lines or acting according to the mood of the scene.

Your last three films have begun in very familiar genres - the serial killer movie, the monster movie, the murder mystery - before expanding beyond the boundaries of those genres. Do you enjoy working in these genres because they allow you to subvert the audience’s expectations?

I have complex feelings about genre. I love it and I hate it at the same time. I have the urge to make audiences thrill with excitement of the genre, while I also try to betray and destroy the expectations of the genre. However, to be frank, I’m not really conscious of the genre itself every time I work. My favourite genre lies inside myself, and as I follow my favourite stories, characters and images, it consequently ends up in a certain genre. So at times even I have to try to guess which genre it’ll be after production. Frankly speaking, that’s the reality.

One of the key themes in your work is the effect of violence on families and communities. Why does this theme interest you?

I’m a little faint-hearted, and I’m afraid of violence. When I experience or witness violence its after-effects last quite long. Especially in Korea, in which I spent my adolescence, the 1970s-80s were days of military dictatorship. In those days, violence was such an ordinary thing. Not only those investigators who tortured suspects, but also at schools, violence was a prevalent thing. I got spanked a lot in school, since teachers' violence against students was nothing so strange at that time. We even had military training at school, so violence was a daily routine. There are still vestiges of it; that’s why we can’t help being interested in the relationship between Korea and violence – this instilled violence.

Mother seems to be heavily influenced by Hitchcock. Is he one of your major filmmaking inspirations? What other directors have influenced you?

When limiting it to Mother, I wasn’t particularly conscious of Hitchcock. I think things like the construction of shots are fundamentally different. I have seen Hitchcock’s Psycho a few times during pre-production. I like seeing my favourite films over a few times, but especially in case of Psycho, there’s the mother who becomes dead and stuffed. Before her death, this mother’s relationship with her son Anthony Perkins seemed quite similar with the relationship with the mother and son in Mother. When commenting on my general filmography, it is likely that I might have been influenced by my favourite directors - Claude Chabrol, who is called a ‘French Hitchcock’, Henri-Georges Clouzot, who influenced Hitchcock’s films. I like those masters of crime films. Japanese director Shôhei Imamura’s crime film Vengeance is Mine is also one of my faves. It is a film about a serial killer which excellently digs up the human nature. I also like Korean director Kim Ki-young who directed the original version of The Housemaid, which was recently remade.

Along with Park Chan-wook and Kim Ki-duk, you were part of an exciting ‘new wave’ in Korean cinema. How do you feel about the current health of the Korean film industry? Are there young filmmakers following in your footsteps who we should look out for in the next few years?

I’m also inside the Korean film industry, so I don’t really have any ideas on how to objectively brief on it. I’m just a tree forming a forest named Korean cinema, and since I lay inside it, it’s hard to view the forest in general. Instead, I can tell you tons of young and talented helmers who deserve attention. There are these genius brother directors named Kim Gok and Kim Sun, also known as Gok Sun-Gok Sa, who are currently preparing for a feature film. Director Lee Yong-ju who directed the impressive horror film Possessed, and director Yang Ik-Joon who directed Breathless, which has gotten spotlights from film festivals overseas. Director Jo Sung-hee, who was awarded at the Cannes Cine Foundation with his short film Don’t Step Out of the House, has also filmed his first digital feature film debut, and I’m anticipating it.

There is both a sequel and a Hollywood remake of The Host in the works. How do you feel about those projects? Do you feel your films are universal and can be adapted to any environment?

Actually, I’ve heard that Universal has bought this film, so perhaps the producer who bought this project might know better than me. I’ve tried to make a ‘Korean film,’ more focused on a Korean sense of emotion. However, some universal aspects of this film might have intrigued them to purchase and remake this film, and I hope it will be an exciting and original remake version. The sequel is also being produced by the same production company – Chungeorahm Film. As thanks for producing The Host, I’ve donated the rights for the sequel to the production company. Personally, I’m much more inclined towards new stories and new films, so I don’t have any interest in sequels or remakes. Anyway, as the original author, I hope whether they are sequels or remakes they all could do well eventually.

What is the current status of Transperceneige? Are there any other projects that you are particularly keen to make in the future?

I’m doing this interview while working on my scenario. I guess an adaptation could be done during August. The project that I want to do...of course, there are tons of them, but there’s one particular project which I’m planning to work on after finishing Transperceneige. It’ll be such a unique one, I think.

Mother is a mystery, but it's also a comedy, a thriller, a satire, a drama, and it both opens and closes with a dance sequence. Most directors would balk at handling such a variety of conflicting tones within a single movie, but Bong Joon-ho is not most directors, and this young Korean filmmaker appears to relish the opportunity to confound and upend audience expectations wherever possible. The first surprise Mother offers is simply how intimate and low-key it feels after the outlandish action of Bong's blockbuster monster movie The Host, but just because the filmmaker is operating on a smaller scale here doesn't mean we should consider his new work a minor entry or a backwards step. In fact, Mother is perhaps the director's most ambitious and emotionally complex work to date, and at its core there is a monster every bit as terrifying and relentless as the creature that rampaged through Seoul in The Host; a woman driven to terrible acts by her obsessive love for her son.

Mother is a mystery, but it's also a comedy, a thriller, a satire, a drama, and it both opens and closes with a dance sequence. Most directors would balk at handling such a variety of conflicting tones within a single movie, but Bong Joon-ho is not most directors, and this young Korean filmmaker appears to relish the opportunity to confound and upend audience expectations wherever possible. The first surprise Mother offers is simply how intimate and low-key it feels after the outlandish action of Bong's blockbuster monster movie The Host, but just because the filmmaker is operating on a smaller scale here doesn't mean we should consider his new work a minor entry or a backwards step. In fact, Mother is perhaps the director's most ambitious and emotionally complex work to date, and at its core there is a monster every bit as terrifying and relentless as the creature that rampaged through Seoul in The Host; a woman driven to terrible acts by her obsessive love for her son.

The mother in the film is never named, but she is played by Kim Hye-ja, an actress famous in South Korea for playing a number of lovable maternal characters. Here she plays a widow who lives alone with her 27 year-old son Yoon Do-joon (Korean heartthrob Won Bin, cast superbly against type). He's an adult but he has the mind of a child, and the mother is fiercely protective of her son, who is rarely allowed out of her sight and still sleeps in her bed. When a teenage girl is found murdered, all of the evidence points squarely at Do-joon, and as he lacks the wherewithal to recall what happened on the night in question or offer a convincing alibi, it is considered an open and shut case. The only person who believes in his innocence is his mother, but as she begins her own investigation, Bong keeps blurring the lines of right and wrong and shifting our perception of who is truly guilty. Again and again we ask ourselves, does mother really know best?

Following the investigation of an amateur sleuth may place Mother firmly in genre territory, but that's how both The Host and Memories of Murder began, and Bong has a way of transcending the boundaries of a given genre by adding unexpected twists to familiar situations. From the very first shot of Mother, Bong throws us off balance, and he never really gives us an opportunity to find our feet again. The film keeps shifting into something new but Bong remains in complete control of the material throughout. It's hard to avoid comparisons to Hitchcock (not only because of the subject matter, but also because of the Bates-like nature of the central relationship), but Bong truly earns such lofty comparisons as his film is crafted with stunning precision. He has a superb sense of visual composition, and Mother contains so many shots that are strikingly inventive, both in the way Bong frames his lead actress and captures the society around her; a society full of feckless cops, exploitative lawyers and poor underclass who are shunned and forgotten.

He also crafts scenes of extraordinary, knife-edge tension, and one particular sequence here – in which the mother is caught unawares as she investigates a potential suspect's home – is a masterpiece of staging and editing. However, while Bong is willing to plunge into the darkest and most gripping aspects of his story, he is always ready to find humour in the same places. His films are constantly teetering on the edge of farce, but the remarkable thing about this director is how he manages to sustain that balance and hit just the right note every single time. There's always room in his stories for the foibles and eccentricities of ordinary people, and I can't think of another filmmaker who handles drastic tonal shifts with such adroitness and confidence.

Mother keeps us guessing all the way, as does Kim Hye-ja's formidable lead performance. She perfectly expresses the deep love she possesses for her son, but there's a flash of madness in those eyes and Bong frequently holds his camera on her face, inviting us to explore it for a clue to her thoughts and feelings. It's a fearless piece of acting that traverses so many emotions, and perhaps that emotional core, a new development in Bong's work, is the key element that elevates this picture above his already exceptional oeuvre. It is derived from the deep maternal bond that forms the movie's backbone, and it reaches its full expression in the final 15 minutes when Bong, after a terrific late twist, turns his film into a study of guilt, as the mother finally contemplates the true cost of her actions. Mother has ended in a place that we never could have envisaged at the movie's start, but everything that has happened has felt organic and inexorable, and all that's left for us to do is to sit back and gaze in awe at the breathtaking final shot that Bong closes his film with. It's shots like this that confirm just how good this guy is. Bong Joon-ho is a master filmmaker, and Mother is a masterpiece.

Read my interview with Bong Joon-ho here.

Near the start of The Expendables, one member of the titular mercenary group, played by Dolph Lundgren, threatens to hang a Somali pirate by the neck and is subsequently admonished by the team's leader Barney (Sylvester Stallone). "We don't kill people that way," Barney reminds him, which sounds like a noble sentiment, but when you consider the myriad ways in which The Expendable do kill people, it rings pretty hollow. During the course of Stallone's latest film people are riddled with bullets, dismembered, set on fire, stabbed and decapitated – in fact, Stallone's cry for restraint comes mere moments after Lundgren's Gunner Jensen has blown the top half of a person to pieces, leaving his legs standing beneath a bloody hole.

Near the start of The Expendables, one member of the titular mercenary group, played by Dolph Lundgren, threatens to hang a Somali pirate by the neck and is subsequently admonished by the team's leader Barney (Sylvester Stallone). "We don't kill people that way," Barney reminds him, which sounds like a noble sentiment, but when you consider the myriad ways in which The Expendable do kill people, it rings pretty hollow. During the course of Stallone's latest film people are riddled with bullets, dismembered, set on fire, stabbed and decapitated – in fact, Stallone's cry for restraint comes mere moments after Lundgren's Gunner Jensen has blown the top half of a person to pieces, leaving his legs standing beneath a bloody hole.

So perhaps one might say that The Expendables' moral code is somewhat uncertain. You could also fairly argue that it's a movie populated by one-dimensional characters, full of cheesy dialogue and driven by a simplistic plot. On paper, it sounds risible – a testosterone-fuelled last hurrah for a macho bunch gaining a temporary reprieve from straight-to-DVD purgatory – but I'd be lying if I said I didn't have a lot of fun watching it. The question is, why did I get so much enjoyment from this film despite its flaws, when I so recently loathed Joe Carnahan's similarly styled The A-Team? Maybe it's simply a case of honesty. Whereas The A-Team was coated with a smug layer of self-consciousness, The Expendables feels more upfront about its aims. Stallone and co. have set out to make a real, old-fashioned action movie, delivered without a hint of irony, and for better or for worse, that's exactly what it is.

Stallone seems determined at every turn to give the fans what they want, and if the atmosphere at the screening I attended was any indication, the fans will love what he's giving them. Each member of the absurdly muscular cast list received his own cheer as their credit appeared on screen, and the audience went wild during the much-publicised 'Planet Hollywood' scene, which reunites Stallone with Bruce Willis and The Governator himself. Beyond giving the viewers a few chuckles, the purpose of this scene is to lay out the upcoming mission for Barney and his team. They're asked to liberate a small South American island which is being ruled by a harsh dictator, but when Barney and right-hand man Lee Christmas (Jason Statham) recon the location, they realise General Gaza is just a puppet, and American drug kingpin Monroe (Eric Roberts, on fine villainous form) is the man holding the strings.

It's an impossible mission, and The Expendables are ready to walk away, but the capture of local girl Sandra (Giselle Itié) prompts Barney to do a little soul-searching. At least, I think that's what he's doing – the fact that Stallone's rubbery features tend to settle into the same weary expression no matter what he's supposed to be feeling tends to undermine his stabs at emotional depth. Ultimately, the film is held together by the camaraderie of its central team, and there's no doubt that this cast is The Expendables' trump card. Stallone does a commendable job of marshalling his actors (Rourke, Roberts), action stars (Statham, Lundgren, Jet Li) wrestlers (Steve Austin, Randy Couture) and one ex-footballer (Terry Crews) into a cohesive unit, and his democratic direction gives everyone an opportunity to shine. The revelation of the movie is Lundgren, who is surprisingly terrific as drugged-up wildcard Gunner, but it's Statham who emerges as the film's true star.

Statham is at the centre of the best sequences, from the air assault on General Gaza's army to a fight on a basketball court that comes with a funny punchline, and Stallone directs these scenes with a satisfying sense of efficiency. Actually, that's the most pleasing thing about The Expendables as a whole; the film is so direct, straightforward and unencumbered by anything superfluous to the action. It's a tight and surprisingly smooth experience, and Stallone – clearly aware of the risk that his film might outstay its welcome – keeps things moving all the way up to the explosive climactic battle. As I watched this ending (during which Stallone and his crew blow up everything), I realised that the film's ludicrous action and old-school sensibility had managed to keep me entertained, amused and occasionally excited for 100 minutes. It may not be great art, but taken on its own unashamedly unreconstructed terms, The Expendables surely has to be considered a roaring success.

For about half an hour, as I watched Black Dynamite, I was convinced that I was watching one of the films of the year. Scott Sanders' movie is a spot-on spoof of 70's Blaxploitation cinema, and its blend of uncanny genre pastiche with deadpan humour is probably the most potent such mix since the heyday of Airplane! and The Naked Gun. The title character (played by Michael Jai White, who also co-wrote) is a Shaft-like investigator who is out to avenge his brother's death, clean up the streets, and stick it to The Man, and as he goes on a wildly convoluted journey, Sanders and his production team lovingly recreate that era's cinema with a bewildering attention to detail. Technically, this film is a flawless piece of work. I just wish it had enough jokes to fill out its 80-minute running time.

For about half an hour, as I watched Black Dynamite, I was convinced that I was watching one of the films of the year. Scott Sanders' movie is a spot-on spoof of 70's Blaxploitation cinema, and its blend of uncanny genre pastiche with deadpan humour is probably the most potent such mix since the heyday of Airplane! and The Naked Gun. The title character (played by Michael Jai White, who also co-wrote) is a Shaft-like investigator who is out to avenge his brother's death, clean up the streets, and stick it to The Man, and as he goes on a wildly convoluted journey, Sanders and his production team lovingly recreate that era's cinema with a bewildering attention to detail. Technically, this film is a flawless piece of work. I just wish it had enough jokes to fill out its 80-minute running time.

Black Dynamite runs out of steam like you wouldn't believe in its second half, which is a damn shame because it opens brilliantly. Sanders sets the tone early on, introducing his hero as he pleasures three ethnically diverse women at the same time. When he's finished, they each coo their satisfaction, prompting Black Dynamite to say, "Shh, Mama. You're gonna wake up the rest of the bitches" as he points to the two other women snoozing under the covers. He is the epitome of black male virility and he embodies every possible cliché of the Blaxploitation leading man; he is simultaneously a killer, a lothario, a kung-fu master and a traumatised war veteran. White plays the role dead straight and manages to create a character that is both an archetype and a memorable protagonist in his own right, which typifies the careful balancing act the filmmakers have attempted to achieve here. This is not a spoof in the same vein as the atrocious Jason Friedberg/Aaron Seltzer films, which lazily cobble together references for a cheap laugh of recognition. Instead, it is closer in spirit to something like Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein, a film that both sends up its genre while offering a thoroughly convincing facsimile of it.

Sanders never wavers from the 70's aesthetic. Car chases are filmed with the aid of rear projection, stock footage is clumsily cut into the action (often more than once) and the fights are hilariously unconvincing. The boom mic keeps dropping into shot (at one point, it nestles atop White's afro as he tries to deliver a monologue) and there are continuity errors aplenty, the most startling of which sees one actor being replaced by another mid-scene. This might sound like a compendium of easy targets, but I don't want to undersell the quality of Black Dynamite's painstaking homage. Shawn Maurer's Super 16 cinematography perfectly replicates the crudely lit and washed-out look of cheap 70's movies, with his camera often zooming clumsily to find the focus of the scene. The production design is convincing, and Adrian Younge's music – including the repeated motif "Dy-no-mite! Dy-no-mite!" – is perfectly in tune with the times. Everything just feels so right.

So where does it all go wrong? It's hard to pinpoint exactly, but before the film had even reached the hour point I was beginning to feel the strain. Too many of the jokes in the film's final two-thirds are variations or repetitions of jokes spun in the opening third, and when the gags start to dry up, the 'plot' – outlandish and overwrought as you'd expect – proves to be an unworthy substitute. The drawn-out fights begin to feel rather interminable by the end, and I couldn't help feeling that there's a short film masterpiece buried in here somewhere. Still, Black Dynamite has some truly inspired sequences (the deduction scene involving Greek and Roman mythology is priceless), and even if the laughs aren't evenly distributed, I don't think I can be too hard on a movie that can deliver a line like "Doughnuts don't wear alligator shoes" and keep a straight face.

The posters for The Human Centipede (First Sequence) carry the tagline 100% medically accurate. That's a bold claim to make, and I must admit I'm more than a little sceptical about its validity, but I'm not sure I'm really willing to spend enough time thinking about the logistics and feasibility of this premise to disprove it. Director Tom Six clearly has spent a lot of time mulling over the possibility of stitching together multiple people to create a single entity though, and that's the basis of this bizarre feature. The Human Centipede is the story of a madman who dreams of taking three people and sewing them together, mouth to anus, so food that is ingested by the first person will be digested and passed through the unfortunate soul in the middle before being excreted by the third party. Why? Don't ask me, I'm not the nutcase around here.

The posters for The Human Centipede (First Sequence) carry the tagline 100% medically accurate. That's a bold claim to make, and I must admit I'm more than a little sceptical about its validity, but I'm not sure I'm really willing to spend enough time thinking about the logistics and feasibility of this premise to disprove it. Director Tom Six clearly has spent a lot of time mulling over the possibility of stitching together multiple people to create a single entity though, and that's the basis of this bizarre feature. The Human Centipede is the story of a madman who dreams of taking three people and sewing them together, mouth to anus, so food that is ingested by the first person will be digested and passed through the unfortunate soul in the middle before being excreted by the third party. Why? Don't ask me, I'm not the nutcase around here.

The nutcase is actually Dr Heiter (Dieter Laser), a German surgeon who has already experimented on dogs (a gravestone in his garden reads 'My Beloved 3-Dog') and is now on the hunt for human prey. Luckily for the crazy doctor, his prey is about to come to him, as two irritating American tourists (Ashley C. Williams and Ashlynn Yennie) have broken down in the woods nearby, and are nervously making their way through the darkness to knock on his door. They're going to form the middle and back end of the doctor's creature, with the front part being taken by a Japanese man (Akihiro Kitamura) who speaks no English but spends the whole movie screaming at the top of his lungs anyway. If you're wondering what happens when our Japanese friend needs to defecate...well, don't worry, the director has got that covered.

To be honest, The Human Centipede is actually a lot more repulsive to talk about and to think about than it is to watch. Aside from a few short scenes of surgery, Six spares us from seeing the gory details of the victims' predicament. When stitched together, they are heavily bandaged and all we can see are the scars on the cheeks of the women, with their terrified eyes being visible just above the rear end of the person in front. The fact that The Human Centipede pulls off its central idea without looking entirely ridiculous is testament to the direction of Tom Six, who draws both tension and darkly amusing moments from his setup. The film frequently betrays its low budget and Six embraces many clichés of the horror genre, but his direction skilfully maintains an atmosphere of creeping dread throughout.

He is also aided enormously from the performance of Dieter Laser as the Frankenstein-like figure who orchestrates this sick experiment. He looks every inch the mad scientist, with his pale skin and the insane stare in his eyes, and the effectiveness of his display makes up for the lack of characterisation of his victims, who exist only to suffer and wail in an annoying fashion (it comes as something of a relief when the female characters lose the ability to speak). Ultimately, The Human Centipede is not the watch-through-your-fingers shocker you might be bracing yourself for before viewing (in the coprophilia and humiliation stakes, it certainly falls far short of something like Salò) but it works as a weirdly engrossing little B-movie with some imaginative touches. I can't quite see how Six plans to develop this idea further, but there is a second instalment in this story already in the works, with The Human Centipede II (Full Sequence) set for release in 2011. And the tagline for that one? 100% medically INaccurate. The mind boggles.

A great piece of casting is the main reason François Ozon's Le Refuge works as well as it does. In the central role of Mousse, Ozon has cast Isabelle Carré who, aside from being a fine actress, was heavily pregnant throughout the film's shoot. At the start of the picture, Mousse and her boyfriend Louis (Melvil Poupaud) are drug addicts and the opening scene finds them injecting a fateful overdose of heroin. Mousse later wakes up in hospital, but Louis is not so lucky, and after being informed of her lover's death, Mousse then discovers that she is carrying his child. Louis' wealthy family put pressure on her to have an abortion, but she refuses and leaves for an isolated country house, where she can prepare for the birth of her baby, the last piece of Louis she possesses.

A great piece of casting is the main reason François Ozon's Le Refuge works as well as it does. In the central role of Mousse, Ozon has cast Isabelle Carré who, aside from being a fine actress, was heavily pregnant throughout the film's shoot. At the start of the picture, Mousse and her boyfriend Louis (Melvil Poupaud) are drug addicts and the opening scene finds them injecting a fateful overdose of heroin. Mousse later wakes up in hospital, but Louis is not so lucky, and after being informed of her lover's death, Mousse then discovers that she is carrying his child. Louis' wealthy family put pressure on her to have an abortion, but she refuses and leaves for an isolated country house, where she can prepare for the birth of her baby, the last piece of Louis she possesses.

It's clear that the fascination in this story for Ozon lies very much with his leading lady. He makes great use of Carré's naturally bulging belly and swelling breasts, and other characters in the film seem to find them just as transfixing as the director does. Le Refuge is an extremely tactile film, with people constantly reaching out to touch Mousse's stomach; when she meets a man who asks her to go to bed with him, she responds by requesting that he simply hold her and another scene has Mousse encountering a rather intense woman on the beach. There's a great tenderness in the film overall, with Mathias Raaflaub's delicate cinematography bringing a sense of peacefulness to the scenes at Mousse's retreat, particularly when compared with the harsher shooting style in the early Paris-set scenes, and Ozon, who has always been a great director of women, draws a superb display from Carré. She's a mesmerising screen presence who is especially watchable in her character's quieter, more contemplative moments, but after a while I began to wonder if there was much more to the film beyond this strong central performance.

In truth, I'm not sure there is. Mousse is eventually joined at her refuge by Louis' younger brother Paul (Louis-Ronan Choisy), and the pair's developing friendship is troubled by the resemblance to Louis that Mousse sees in him. Choisy is a musician rather than an actor (he also contributed the lyrical score), and he never really brings his character to life. The film rather drifts through its second half as this central relationship grows more complicated, but Ozon's understated approach fails to engineer any kind of dramatic momentum. Le Refuge builds to a climax that is both surprising and touching, but it still feels like a minor piece of work from a talented director. Frankly, I'm a little disappointed that of the two films Ozon made in 2009, this is the one that's receiving a UK release while his other feature Ricky (about a flying baby, no less!) failed to get distribution.

My mind has a tendency to wander when the film I'm watching isn't sufficiently engaging, and as I sat in front of Knight and Day, my thoughts kept drifting back to the title. Knight and Day – what does that even mean? Before the film, I had assumed that these might be the surnames of the lead characters played by Tom Cruise and Cameron Diaz, but they're actually called Roy Miller and June Havens. Wait a minute, it turns out I was half right, as Roy's real name is revealed to be Knight halfway through the film, and then there's that whole business about hiding the MacGuffin everyone's after in a toy knight, but that still doesn't explain the Day bit...oh, I suppose it's really not worth thinking about. Still, at least I had something to ponder as this increasingly tedious movie went about its business.

My mind has a tendency to wander when the film I'm watching isn't sufficiently engaging, and as I sat in front of Knight and Day, my thoughts kept drifting back to the title. Knight and Day – what does that even mean? Before the film, I had assumed that these might be the surnames of the lead characters played by Tom Cruise and Cameron Diaz, but they're actually called Roy Miller and June Havens. Wait a minute, it turns out I was half right, as Roy's real name is revealed to be Knight halfway through the film, and then there's that whole business about hiding the MacGuffin everyone's after in a toy knight, but that still doesn't explain the Day bit...oh, I suppose it's really not worth thinking about. Still, at least I had something to ponder as this increasingly tedious movie went about its business.

I guess Knight and Day isn't an awful film by the standards of the usual mainstream summer movie, but it's so painfully average in every department. It wants to be both an explosive action blockbuster and a screwball comic romance, but the sheer desperation of all involved, as they strain to please the mass audience, practically drips off the screen. Unsurprisingly, the film is a conflicted mess that is neither exciting enough or funny enough to succeed in any of the genres it strays into, and after the first hour has elapsed, the endless superficiality and senselessness of the whole production becomes exhausting.

Most frustratingly, this is a project that had some potential, and the first 15 minutes or so are intriguing and occasionally funny. Cruise's Roy and Diaz's June meet-cute at an airport before trading some flirtatious banter on the flight, and when she excuses herself to freshen up, he quickly despatches the agents on board that have been sent to kill him. It turns out he's a spy who has gone rogue to protect a young scientist (Paul Dano) from the traitorous FBI man (Peter Sarsgaard with an unnecessary accent) who wants to sell his invention to a notorious arms dealer. At least, that's his story, but the agency's claims that Cruise is a loose cannon who has lost the plot may be true for all June knows. Either way, she's now mixed up in whatever plot he's involved in, and despite her efforts to extricate herself from this adventure, she ends up following Roy from Boston to South America, via Austria, Spain and a remote tropical island.

However, it doesn't matter where they go because Roy and June just end up getting involved in another chase sequence and/or fight at every stop. James Mangold's direction is competent enough, but it lacks the liveliness and invention needed to give these action set-pieces a distinctive edge. Instead, we just watch as the seemingly invulnerable Roy wipes out dozens of assailants while June screams and flaps her arms and accidentally takes out the odd assassin herself. When they find themselves in a particularly tight spot, the scene sometimes ends with Roy drugging June, before she wakes up in an entirely new location, with no idea of how they managed to get there. Mangold uses these ellipses to move his story forward, but they end up leaving huge gaps in the narrative, giving the film a disjointed, slapdash structure that actually disrupts the momentum. Knight and Day feels hastily thrown together, a sense that's exacerbated by the shoddy effects work noticeable in a number of sequences, and it's clear that the filmmakers are banking heavily on the picture's star power being enough for audiences to overlook its flaws.

The gamble doesn't come off. Roy Miller is actually a good fit for Cruise and he brings his customary full-on intensity to the role, giving the character a slightly manic air that is clearly intended as a nod to his public persona. It's a decent performance, but he only has a single note to play for the whole movie. Diaz has her amusing moments as June (the truth serum scene being a highlight), but her performance is generally as strained as much of her recent work has been – where is the light radiance that made her such a star in the 90's? Ultimately, the terminal blow for the film is the complete lack of spark between its two stars. No matter how often they flash their blindingly white teeth at each other, we never believe in these characters or their relationship, and so Knight and Day just plays out as another empty mainstream dud; a film that has money to burn but hasn't taken the time to put in place the basic building blocks of a solid picture. In the right hands, Knight and Day could have worked, but it would have required a complete overhaul of personnel, scale and focus. They should have started with the title.

There's a double meaning behind the title The Secret in Their Eyes. On one level, Juan José Campanella's film is a love story, and the title therefore refers to the way Benjamín Esposito (Ricardo Darín) and Irene Menéndez Hastings (Soledad Villamil) gaze longingly at each other. The emotions they feel may have gone unspoken for years, but for anyone watching them together, it's pretty much an open secret. Primarily, however, The Secret in Their Eyes is a thriller, and here the title refers to the way a suspect gives himself away through the direction of his glance in an old photograph. Unfortunately, this is indicative of the rather contrived plotting that plays a part in undermining this classily made picture.

There's a double meaning behind the title The Secret in Their Eyes. On one level, Juan José Campanella's film is a love story, and the title therefore refers to the way Benjamín Esposito (Ricardo Darín) and Irene Menéndez Hastings (Soledad Villamil) gaze longingly at each other. The emotions they feel may have gone unspoken for years, but for anyone watching them together, it's pretty much an open secret. Primarily, however, The Secret in Their Eyes is a thriller, and here the title refers to the way a suspect gives himself away through the direction of his glance in an old photograph. Unfortunately, this is indicative of the rather contrived plotting that plays a part in undermining this classily made picture.

"I can't look back. Backwards is out of my jurisdiction," Irene tells Benjamín, but he can't help peering back into the past. In 1974, they were both investigators working on a brutal rape and murder case, and 25 years later, the now-retired Esposito is still haunted by the details of this crime, which he's hoping to incorporate into the novel he's writing. Campanella handles the parallel narratives that unfold in separate time periods with some grace, and The Secret in Their Eyes generally flows beautifully, with the director imposing a steady pace on the picture that benefits both the police procedural aspect of his tale as well as the slow-burning romance. That romance is given weight by the two leads as well, with the ever-excellent Darín and the entrancing Villamil sharing an onscreen chemistry that is one of the film's most notable successes.

Beyond the details of the main story, Campanella clearly intends The Secret in Their Eyes to have some larger resonance, with the events of the narrative acting as a metaphor for the climate of fear and retribution that festered in Argentina before the rise of the military junta. That's all well and good, but the film ultimately struggles to convince on a much more basic level. I'm not sure how strictly the director adheres to Eduardo Sacheri's source novel (presumably it is a faithful adaptation, with Sacheri being credited as co-writer), but much of the film is hobbled by the kind of thriller novel plotting that is often exposed on the big screen. The aforementioned identification of a suspect by his sideways glance in a photo is one particular groaner, and the further location of his whereabouts by his habit of constantly referring to players from his favourite football team is another. By the time the villain had been conned into a confession through a stupidly obvious interrogation tactic, I was starting to lose interest, but these developments have nothing on the climactic twist, which is laughable on a number of levels.

It seems to have worked for a lot of people, however. The Academy voters certainly fell for The Secret in Their Eyes in a big way, surprisingly awarding it the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar ahead of such big-hitters as A Prophet, The White Ribbon and Ajami. In retrospect, perhaps we shouldn't be so surprised, as it's exactly the sort of picture the Academy likes to choose in this category; stylishly made, with a surface sheen of complexity but resolutely old-fashioned and conventional at heart - it's 2010's The Lives of Others. There's no denying that the picture is beautifully made, with Campanella showing absolute assurance and confidence in his direction, and Félix Monti providing some outstanding cinematography, but I found precious little to get excited about.

There is one scene in The Secret in Their Eyes that really got my pulse racing, however. It occurs in a packed football stadium, where Esposito and his partner Sandoval (Guillermo Francella, bringing life to a thin part) finally come face-to-face with their target. The scene begins with a swooping helicopter shot before segueing seamlessly into a thrilling chase through the crowd and the stadium corridors, which is achieved through some extraordinarily inventive camerawork and faultless editing. It's an unashamedly flashy sequence, and one that threatens to draw attention to the technique rather than the content, but I found it dynamic and gripping and a real shot in the arm for the film. Unfortunately, this scene also feels like it has been parachuted in from a completely different movie, and as soon as it's over, the rest of The Secret in Their Eyes struggles futilely to match up to it.

Despite the best efforts of a talented cast and an ambitious first-time director, Beautiful Kate never rises above the dreary familiarity of its subject matter. The film is a rather strained tale of family strife in Australia, with Ben Mendelsohn starring as Ned, a successful author returning to the remote family home he grew up in for the first time in twenty years. There, he will have to face his tyrannical father Bruce (Bryan Brown), but the greater challenge for Ned is to face the ghosts that haunt this house, with every item reminding him of the tragedy that befell his twin sister, the eponymous Kate (Sophie Lowe), when they were both teenagers. Director Rachel Ward refuses to draw boundaries between the past and the present throughout the film, with memories of Kate intruding on Ned's consciousness at every turn. For Ned, there is no escape from the past.

Despite the best efforts of a talented cast and an ambitious first-time director, Beautiful Kate never rises above the dreary familiarity of its subject matter. The film is a rather strained tale of family strife in Australia, with Ben Mendelsohn starring as Ned, a successful author returning to the remote family home he grew up in for the first time in twenty years. There, he will have to face his tyrannical father Bruce (Bryan Brown), but the greater challenge for Ned is to face the ghosts that haunt this house, with every item reminding him of the tragedy that befell his twin sister, the eponymous Kate (Sophie Lowe), when they were both teenagers. Director Rachel Ward refuses to draw boundaries between the past and the present throughout the film, with memories of Kate intruding on Ned's consciousness at every turn. For Ned, there is no escape from the past.

This tactic of allowing the film to flow freely between different time periods is a daring one for Ward to employ, but it has the unfortunate effect of making things feel slightly aimless, whereas a director with a firmer hand may have given the picture more shape. Many of these flashbacks are shot from the point of view of young Ned (the well-cast Scott O'Donnell), although Ward drops that gambit around halfway through the film in favour of a more conventional and less distracting shooting style. Ned is haunted not only by his sister's death but by the incestuous relationship they shared the summer that she died, and Ward handles this difficult plot strand with skill and sensitivity, drawing fine performances from both O'Donnell and Lowe. Lowe gives an especially impressive turn as the enigmatic Kate, her vivacious presence and ability to handle sharp emotional shifts ensuring this character draws us in even as she remains intriguingly unknowable.

Ward is strong with actors on the whole, and their excellent work is crucial in propping up a film that occasionally threatens to lose its way. As Ned's sulky young fiancée, Maeve Dermody is short-changed by the thinness of her characterisation and by the unconvincing nature of her relationship with Ned, but she manages to give a sparky performance while the other three leads do the emotional heavy lifting. Rachel Griffiths gives solid support in a disappointingly small role, but it's Bryan Brown who really impresses as the dying patriarch still filled with rage and spite even as his body slowly wastes away.

For all of this ensemble's hard work, however, Beautiful Kate is ultimately lacking in the deep emotional impact a story like this is reaching for, and part of this is down to the directorial choices Ward makes. The cinematography by Andrew Commis is gorgeous in places, but the hazy style seems to keep us at an emotional remove from the drama, as does the ever-present and slightly grating score. The other problem Beautiful Kate has is that Ward misjudges the point where her tale tips over into melodrama, and the final revelation of a secret kept for twenty years is a real misstep, which gives the film nowhere interesting to go in its closing scenes. This is a beautiful and lovingly crafted piece of work, but it's also the work of a filmmaker struggling to find the balance between style and substance, and it ends up feeling like a rather empty endeavour.

"What's the worst that could happen?" That question comes up a couple of times in Splice, and it's usually the precursor to another unpleasant development. Vincenzo Natali's latest film is full of gory surprises, and while they may be unpleasant ones for his lead characters, they tend to be very enjoyable ones for the audience. Perhaps the biggest surprise of all is the fact that Splice coheres as well as it does, given the fact that it's something of a hybrid itself, drawing on a variety of cinematic influences and blending disparate tones. Of course, from the moment scientists Clive (Adrien Brody) and Elsa (Sarah Polley) begin mucking around with genetics in an unauthorised experiment, you know exactly how Splice is going to end, but you're still likely to have a lot of fun with the weird twists and turns that Natali takes en route.

"What's the worst that could happen?" That question comes up a couple of times in Splice, and it's usually the precursor to another unpleasant development. Vincenzo Natali's latest film is full of gory surprises, and while they may be unpleasant ones for his lead characters, they tend to be very enjoyable ones for the audience. Perhaps the biggest surprise of all is the fact that Splice coheres as well as it does, given the fact that it's something of a hybrid itself, drawing on a variety of cinematic influences and blending disparate tones. Of course, from the moment scientists Clive (Adrien Brody) and Elsa (Sarah Polley) begin mucking around with genetics in an unauthorised experiment, you know exactly how Splice is going to end, but you're still likely to have a lot of fun with the weird twists and turns that Natali takes en route.